Art Class With Leibniz

Recently I decided to try out Jax, Google's new library for differentiable programming. Essentially Jax allows you to take arbitrary derivatives of python. It claims to be simpler and more flexible than competing frameworks such as pytorch or tensorflow. It uses a fancy just in time compiler and auto parallelization to make your code faster. Since the easiest way for me to learn is by working, I thought about problems I could tackle with Jax.

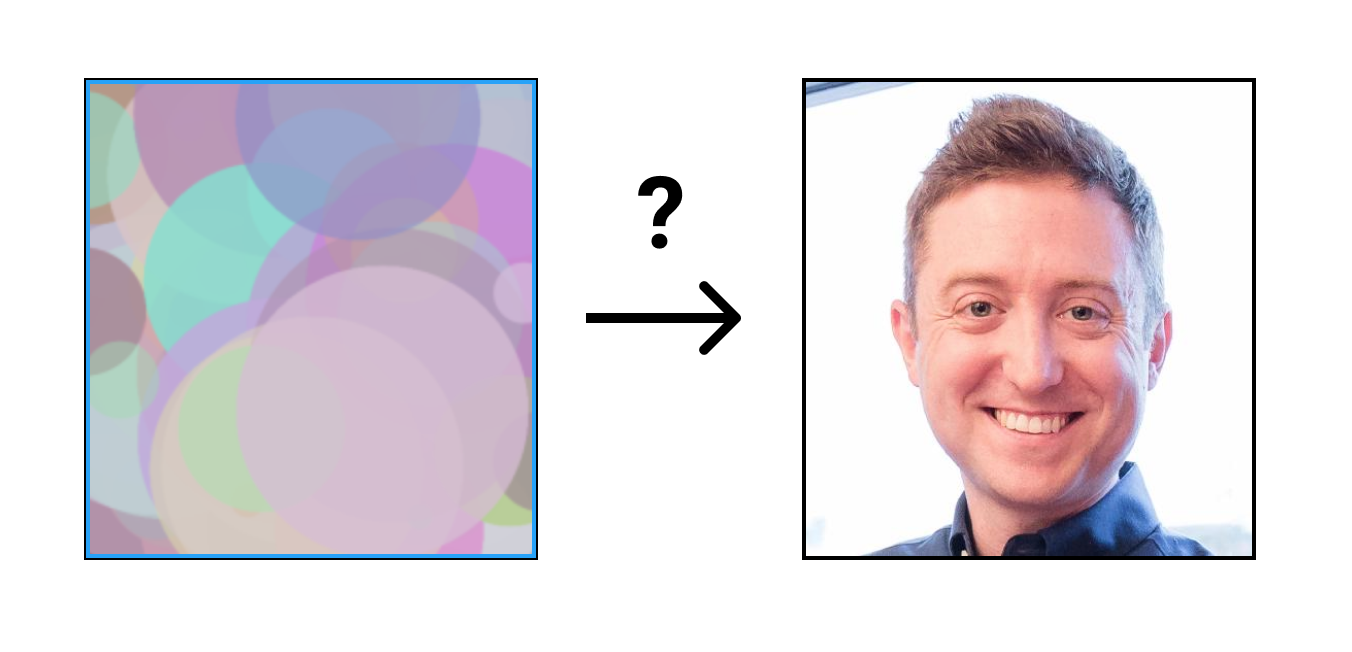

Inspired by impressionist painting I decided to try to answer the question, "how well can I represent an image with a fixed number of circles?" To give a more exact definition suppose we have n colored circles each having 7 parameters: x position, y position, radius, red, green, blue and alpha (transparency). Each circle also has a (non adjustable) depth which is used to determine which circle occludes another should they overlap. Here's a picture of 100 of these circles whose parameters have been randomly initialized rendered against a black background.

The goal of this project is to find values for these parameters which minimize the squared error between the image made of circles and a target image. Throughout most of this project that target image happened to be frequent jax contributor Mattjj's avatar because I was seeing it in every github issue.

So how do we tackle this complex optimization problem? That's right, we're just going to use gradient descent by differentiating through the rendering process.

Okay so what does that actually mean?

Let's say we have a function which takes in our circles and draws them onto an image:

We can make a loss function which takes in circles and outputs the loss between the rendered image and our target image:

With the magic of Jax we can create a function which gives us the gradient of our loss function with respect to its parameters (the circles) by simply saying:

This line of thought is an extremely simplified version of differential rendering techniques but instead of writing a fully functioning 3d differential renderer from scratch we're just gonna approximate some guy's face with circles.

Now we just need to fill in our render function from above with a way to get from circles to pixels. The rendering technique that I used was pretty simple. All I did was start with a blank canvas then I looped over each pixel and looped through all the circles in back to front order. If a circle intersected the pixel in question I would blend it with the current r,g,b values of that pixel which came from the circles behind it.

Jax the Sharp Bits

The jax documentation has a section called "Jax the Sharp Bits" which I ended up visiting very frequently during this project. Inspired by that, instead of just presenting the final method I'm gonna to dig through my memories (and git history) to tell the tale of how I fought with Jax to build this over the last week. If you don't want to see jax specific details, I'd skip to Math the Sharp Bits or Results.

First Attempt

As stated above I took a very simple approach for the render function you can take. I used python's for loops to iterate over the width and height of the canvas and at each pixel I checked if the pixel in question intersected each circle (in back to front order). If it did I modified the pixel's color according to linear alpha blending rules: (1 - alpha) *previous color + alpha*new color.

The code looked like this:

Unfortunately as many people who have tried to use python for computationally intensive tasks can tell, this code was extremely slow (about 10s for one render call on my 2015 Macbook Pro).

Luckily, Jax claims to address these problems for repeatedly called routines through it's jit (a special kind of code optimization process). In theory one can just call jit(render) to get a jitted version of the render function. However translating the render code to fast jit-able jax code was not exactly that straight forward.

Pitfall 1

The code above will actually throw an error when I try to run it through Jax's jit function. This is due to the conditional in the get_color function. It turns out Jax's jit cannot handle python's if statements so they provide their own jax.lax.cond function which you can use instead.

Pitfall 2

After getting the function to jit I noticed it was actually slower than the original function. This was really disappointing, however I learned it is because jax unrolls python loops. Mattjj and hawkinsp both have detailed explanations of behavior here and here. Basically Jax does not understand a python loop is a loop and treats each iteration as a distinct logical element producing a giant computation graph. Jax provides jitable functions such as vmap and scan which help prevent this problem.

After fixing these problems the code became pretty usable. Here's what the render function looked like at this point:

I'm not claiming this is the most efficient form of the code but it was now fast enough for me (especially when I discovered I could use a tpu on google colab). If we wanted to make it even faster we could probably implement an intersection acceleration structure like a grid or quad tree so we don't have to check every circle for every pixel. However that would probably also make the code a lot more complex and brittle.

Now I was finally able to generate a real image:

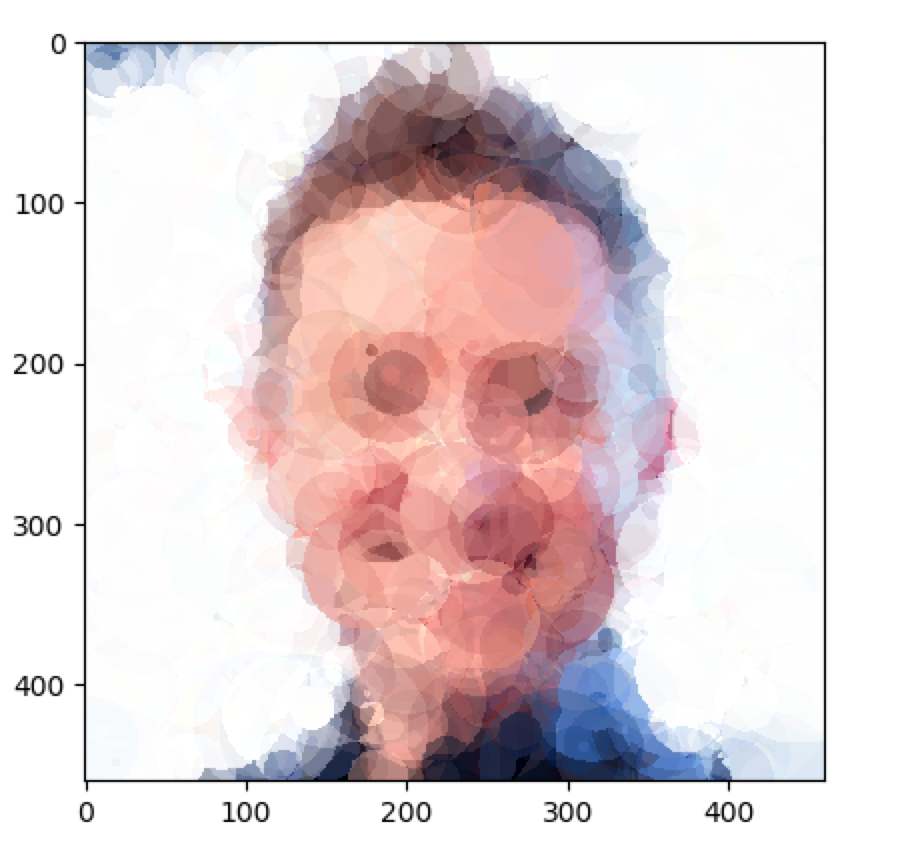

Mattjj approximated with 1000 circles (loss ~4800). I'd recommend stepping back, squinting or viewing these images from an angle to really appreciate some of the blending tricks that are going on.

Looking at the image, 1000 circles seemed like a few too many so I decided to try to push the technique by seeing what it could do with 100 circles.

Math the Sharp Bits

Before I started trying to generate images with fewer than 1000 circles I needed to fix the last few problems with the code that I had been putting off.

First of all, the circles were not moving or changing their size. Even though I was taking the gradient with respect to those parameters as well as the color and alpha values, the gradient of the loss function with respect to position and radius was always zero.

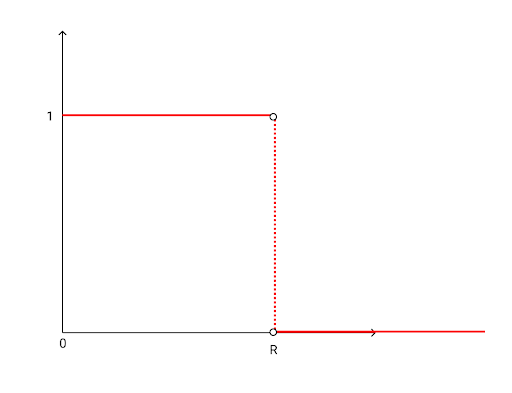

Technically you've already seen the source of this error in my description of the rendering algorithm. However it would have been very hard to catch this error because it was less of a code problem and more of a basic calculus dilemma. The simple way we render circles with a hard cutoff at the edge is not fully differentiable with respect to the position or size.

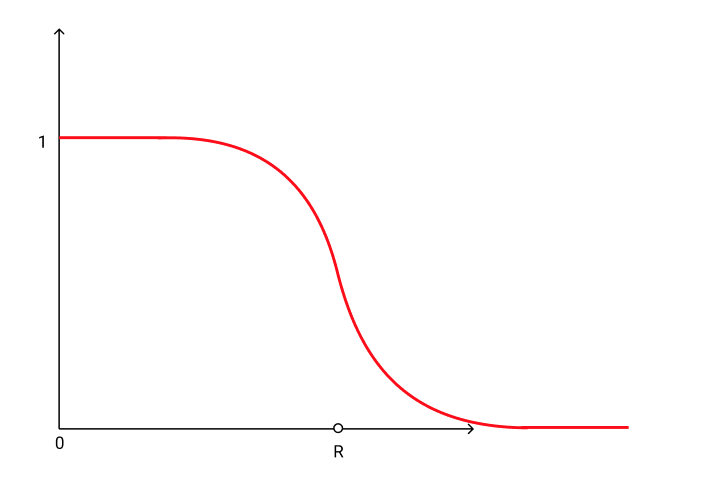

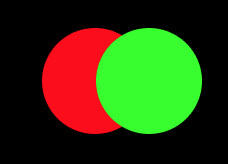

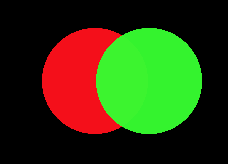

To see why, let's look at a circle's influence on three different pixel positions. For a pixel outside of the circle's radius, the derivative is zero because the circle has no effect on it's color. For a pixel on the inside the circle's effect on the color of the pixel is constant with respect to its size and position so the derivative is still zero. For a pixel at the edge of the circle the derivative is actually undefined. This is a classic example of a heaviside step function. A picture of a radial cross section of the circle's influence on the pixels around below shows the discontinuity.

It turns out some very smart people have put a lot of effort into tackling this problem with edge sampling, fluid mechanics and approximation based approaches.

For our purposes it's easiest to take the approximation path and make our circle's influence fall off with a differentiable function like sigmoid (pictured above) instead of the hard step function. The side effect of this is that our circles get a little blurrier. We also have to introduce a new "softness" parameter that defines how fast our sigmoid function falls off.

So for our purposes we can just replace hard conditional in the line:

with:

Now our renderer is fully differentiable with respect to all the circle parameters.

The last little loose end we have is that currently the red, green, blue and alpha parameters are technically unbounded as well. When you have a sigmoid shaped hammer everything looks like a differentiable nail so I decided to just wrap these parameters in a sigmoid, for example a would become sigmoid(a), which would bound their outputs to [0, 1].

Now I was able to render my first 100 circle image. The gif below shows the optimization process. Notice how all of the circle parameters are being adjusted.

Minibatching

One final optimization I implemented was minibatching (also known as stochastic gradient descent). For our purposes mini batching means only rendering and comparing a random fixed size subset of the pixel at each gradient descent step. I was able to achieve quality results using about 10% of the total samples from before (which greatly sped up the program).

Results

Here are some results generated by this process. All of them can be found in the attached colab notebook where you can see the code and the hyperparameters used to generate them. All final images are rendered with softness = 10.

Also note that we are not optimizing over human perception loss, merely approximating it with the sum of square differences which is not perfect by any means. It seems to me that squinting or viewing the image from other angles makes some of the images (especially the 100 circle ones) look dramatically better. My guess is that this is because our brain stops focusing on the circles allowing us to see the bigger picture. Of course I'm know nothing about the human visual system so take that with a huge grain of salt.

Mattjj

Mattjj 100 Circles

Mattjj 1000 Circles

The Mona Lisa

Mona 100 Circles

Mona 500 Circles

Barack Obama

Obama 100 Circles

Obama 300 Circles

Walter White

Walt 200 Circles

Walt 500 Circles

The Golden Gate Bridge

Golden Gate 200 Circles

Golden Gate 400 Circles

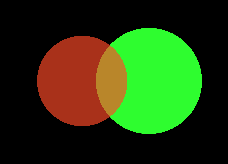

The Mastercard Effect

Honestly I have not had time to do too much analysis of this algorithm (check future questions / ideas for a list of things I wish I had time to do). However I did want to show off one interesting edge case I came across. Inspired by the Mastercard logo this effect demonstrates the optimizer getting stuck in a local minimum.

We will try to approximate the following image with just two circles:

Let's look at the output of our algorithm under two different random seeds:

Seed 1

Seed 2

So what went wrong in the bottom run? It appears that the optimizer colors one circle red and one circle green but the red one is in front of the green one. Unfortunately the algorithm cannot change the order the circles are drawn in so the best solution here would be to recolor the circles. However it appears gradient descent cannot plan far ahead enough to go back and change the colorings. This is because although changing the colorings would lower the loss in the long run it would increase it in the short term. Another way to say this is our optimizer got stuck in a local minimum.

If we had an commutative blend mode like additive blending this would not be a problem. However I think this would limit the amount of colors that could be produced by many overlapping circles which would hurt the algorithm overall.

Future Questions / Ideas

How do the hyperparameters affect image quality?

How does the choice of parameter initalization of the circles affect image quality?

What other loss functions could be used besides L2 (squared error) and how would they affect human perception of images (maybe use the neural style loss)?

Is this method more efficient than simpler hill climbing based approaches?

What if we let the background color be optimized?

What if we used a weighted error function so users could highlight important areas?

What if we attached a neural network to this system and had it learn to place circles in one shot like fast neural style?

What if we used different shapes? What if we let the algorithm choose the shape?

What if we did it in 3d?

Have questions / comments / corrections?

Get in touch: pstefek.dev@gmail.com