Differentiable Dithering

Colab source code can be found here.

Problem

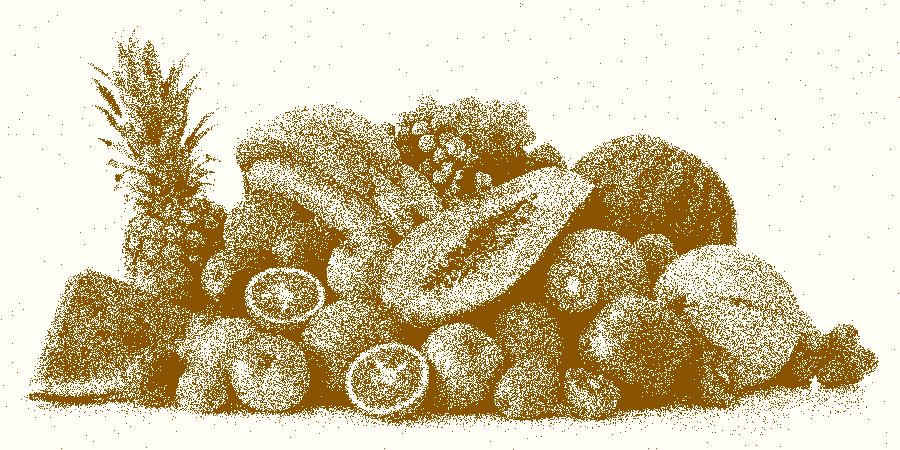

Let's say we want to reduce the number of colors in an image. For example consider the picture of fruit below:

If we run a count of how many colors are in the above image we get a whopping 157376 (for a 900 x 450 pixel image). Are all those colors really necessary?

The image above has 16 colors and the one below only has 8.

The problem of color palette reduction has been studied extensively and the typical approach works roughly as follows:

-

Build a reduced color palette of size N by dividing the color space up into N distinct regions where each region is represented by one color. This is usually accomplished by one of several popular approaches.

-

Dither the image. The process of dithering eliminates color banding and creates the illusion of more colors through a stippling like effect. If you are not familar with dithering we will explore it in more detail later. Given a fixed color palette there are specialized algorithms for dithering such as Floyd Stienberg.

Instead of the usual approach, we are going to solve both of these problems at the same time using gradient descent.

First of all let's define a palette of N colors. For this article the colors will be 3 component vectors in rgb space. A quick warning to graphics nerds, for portability and simplicity we do not take gamma correction into account. Our palette can be thought of as a Nx3 matrix where the rows represent colors in the palette and the columns represent the r,g,b weights of each of those colors. This entries of this matrix are variables in our optimization problem.

Now how do we assign our palette colors to pixels in a differentiable way? I decided to do this using probability distributions. Each pixel is represented by a vector containing the probabilities of each palette color being chosen for that pixel. When actually generating an image we just sample each pixel's color from it's distribution.

The above formulation is pretty general. Importantly both the colors in the palette and the mapping of image pixels to palette colors are variables which we can optimize over simultaneously. Now all we need to do is attach any one of a number of loss functions.

The loss function I chose to use at first was just the squared difference between the original image and the expected value of the output image:

\(loss(output, target)=\sum_{i\in pixels}(target_i\) \(-\) \(E[output_i])^2\) (equation 1)

So what's the idea here? Basically the expected output allows our image to pretend it has more colors than it really does.

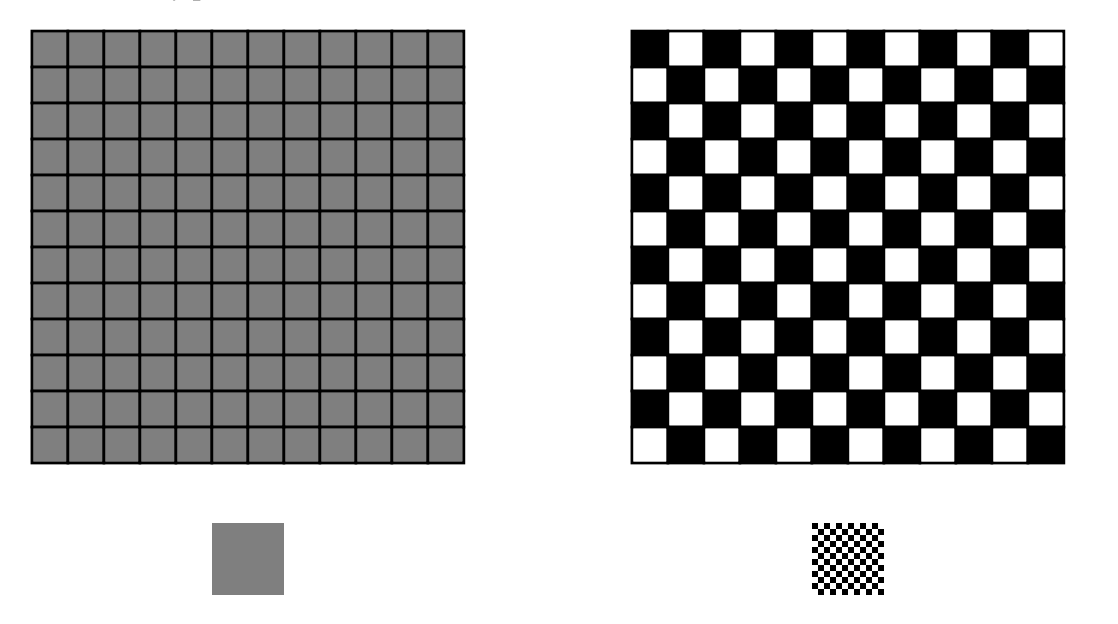

For example let's pretend our palette has only two colors, black and white. Also suppose our target image is a 50% gray square. Consider the following three possible representations of the image. One is an all black image, one is all white and the third has 50% black and 50% white pixels randomly distributed across the image. If we look from far away the third image will look better. This is because the black and white pixels will blur together and appear gray. This effect is called dithering.

By the above reasoning we want to make sure that the dithered pixel assignment (each pixel has a 50% chance of being black or white) should appear more desirable than the other two candidates to our loss function. Taking the squared error between the target image and the expected color of each pixel does exactly this.

You might be asking, why not take the expected value of the whole squared error? This would look like:

\(loss(output, target) = E[\sum_{i\in pixels}(target_i\) \(-\) \(output_i)^2]\) (equation 2)

This actually does not work. To see why, let's look at the same setup as above and consider the expectation of an individual pixel (for math sticklers we can do this because expectation is linear). The loss function for a pixel denoted by the random variable \(X\) that always chooses black is:

\(E[(0.5 - X)^2] = (0.5 - 0)^2 = 0.25\)

And the loss function for a pixel denoted by the random \(X\) which is 50% black and 50% white is:

\(E[(0.5-X)^2] = (0.5-0)^2 * 0.5\) \(+\) \((0.5-1)^2 * 0.5 = 0.25\)

Unfortunately the values here are the same in both cases which rules out this loss function.

Let's try using the loss from equation 1 with a palette of two colors:

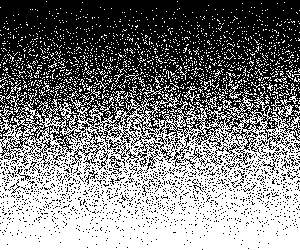

Hey! Not too bad! As we can see, different shades are captured by different densities of darker pixels. For a starker example let's try this image of a vertical black and white gradient:

Now let's try 16 colors:

The above image highlights one weakness of our current loss function. It's very noisy, even when it doesn't have to be.

To give an extreme example, consider an image with three colors red, blue and purple (a mix of 50% red and 50% blue). Let's say we have room for 3 colors in our palette. In the eyes of equation 1 both of the following solutions would have the same loss:

-

The red pixels are red, the blue pixels are blue and the purple pixels are purple. We are using all three colors in our palette to the best of our ability and the image is reproduced perfectly.

-

Each red pixel is red, each blue pixel is blue, each purple pixel has a \(\frac{1}{2}\) chance of being red and a \(\frac{1}{2}\) chance of being blue. Notice here we only use two out of three possible colors and the final image is clearly lower quality.

To control for this weakness, I added an additional term to the loss function which penalizes the sum of the pixel variances with a coeffcient given below by \(c\). The new loss function looks like this:

\(loss(output, target)=\sum_{i\in pixels}(target_i\) \(-\) \(E[output_i])^2 + cVar(output_i)\) (equation 3)

Right now I just hand tune the coefficient of the variance penalty. A good rule of thumb seems to be larger palettes should weigh variance more heavily. Applying this penalty (variance coefficient = 0.25) gives us the 16 color image from the top of this post:

The tradeoff is that too little variance removes too much noise which, due to the absence of dithering, makes the final image appear to contain fewer colors and also creates banding effects. The image below has 16 colors and variance coefficient = 1.0. It demonstrates both of these problems:

In fact when the variance coefficent = 1.0, a little algebra shows equation 3 is equal to our rejected equation 2.

Note there are many valid choices of loss function here and I'm not claiming mine is perfect at all. For example this article on creating optimal dither patterns blurs both images and takes the difference between those. We could try to use this idea or search for something else to replace our simple squared error. It would also be interesting to try to use a real image quality metric like SSIM to measure image quality instead of using variance as a proxy.

Another place for improvement is that our approach is sloooow (up to several minutes). It also does not scale well memory wise to large palettes (when I try using more than 200 colors for the 900x450 pixel fruit image my colab notebook runs out of ram). This is because in that case there are more than 200x950x450 variables to optimize over. We could potentially tackle these problems in two ways. To address speed we could try to break the image up into mini batches. To address memory usage we could try to use a neural network to output probabilities at each pixel location instead of storing them all explicitly.

Why do I think this approach is interesting?

Although this approach is not state of the art by any means in either speed or quality I think it's interesting that we can optimize both the palette selection and dithering at the same time.

As far as I know dithering and palette selection aren't really part of state of the art lossy compression today. However it would be neat if these same concepts could be applied to something like the color space transform, discrete cosine transform and weight quantization steps of jpeg compression.

A pipedream would be an entirely differentiable image compression pipeline where all the steps can be fine tuned together to optimize a particular image with respect to any differentiable loss function.

Have questions / comments / corrections?

Get in touch: pstefek.dev@gmail.com

Discussion on Hacker News.